Editor’s note: In 2013, a book was published by Dr. David LaVere, PhD, a professor of history at UNC-Wilmington, entitled The Tuscarora War. In his book, LaVere references an article that was originally posted at this site and written by Sara Whitford. Although Ms. Whitford’s article was originally published in 2007, when the site was remodeled and moved web hosts a few years ago, that article was one of several items that were not ported over from the original site. When it came to our attention that the article was no longer on the site, we immediately took steps to locate it and repost it.

Editor’s note: In 2013, a book was published by Dr. David LaVere, PhD, a professor of history at UNC-Wilmington, entitled The Tuscarora War. In his book, LaVere references an article that was originally posted at this site and written by Sara Whitford. Although Ms. Whitford’s article was originally published in 2007, when the site was remodeled and moved web hosts a few years ago, that article was one of several items that were not ported over from the original site. When it came to our attention that the article was no longer on the site, we immediately took steps to locate it and repost it.

Case #1: On the Trail of Tom, or A New Look at the Tuscarora War — by Sara Whitford

©2006-2007 All Rights Reserved.

Preface

The following publication examines some new and exciting questions relating to Tuscarora history and the Tuscarora war. First things first: I must give credit where credit is due, as elements of this paper stem from ideas suggested by Charles Shepard and Fred Willard, two individuals with whom I spent some time doing research relating to early colonial Indian history years ago.

When I first met Mr. Willard back in 2004, he opened up an entire new world of research for me by drawing my attention to the old Mattamuskeet reservation of Hyde County. What made the topic even more fascinating were the names in my own family tree that were right off of the list of known names from Mattamuskeet.

Over many conversations, anecdotal bits and pieces of research would come up seeming something like puzzle pieces that unfortunately we did not have a picture to go by in order to solve.

One such subject that offered a few puzzle pieces related to the possibility that Core Tom, a prominent figure in the history of the Tuscarora War, is one and the same as Long Tom of the Mattamuskeet reservation.

All three of us had found various historical records that all mentioned some deviant character named Tom. Loose theories were bounced around, “I wonder if it’s possible that they’re all the same person?” There were even a few instances outside of North Carolina.

Despite the fact that such a theory, if true, would be intriguing, to be perfectly honest, I was quite skeptical of the whole thing. I always kept my eyes open, though, just in case something compelling came up.

Although the three of us had each come across items regarding rogue Toms, we never got around to actually putting our notes together to try to make anything of it.

In 2006, however, I was doing independent research relating to specific elements of the Tuscarora war and the activity of Iroquois in the Carolina territory preceding the war. I stumbled upon the 1697 case and the 1704 case that I cite in this paper. I had seen those before, but had just mentally filed them away to look into at some future time.

So what made me pay closer attention to those cases the second time around?

I was reading Christoph von Graffenried’s account of the trial of John Lawson when I took particular notice of the fact that he seems to clearly identify Core Tom as not only the instigator in John Lawson’s execution, but he also identifies him as “king” of Cartooka (Chatooka), or what is known today as New Bern. This simple fact struck me, because I had always thought of Core Tom as a Coree chief, but how could that be if he was king of Cartooka? Cartooka was a Neusioc village. But then again, Cartooka is also sold to von Graffenried by a Tuscarora council at the point where the Neuse and Trent rivers merge. This place is called “council bluff.”

Why were the Tuscarora selling a village that belonged to the Neusioc?

There were obviously deeper alliances in place, and also a lot of confusing information. I remembered Mr. Willard’s hypothesis on this Core Tom being an indigenous rogue who had just moved from place to place, feeling hostile towards colonials, and striking out at will.

I recalled that Mr. Willard had also mentioned to me years earlier that he seemed to remember someone telling him that, among others, a Susquehannah chief had been at the trial of Lawson and von Graffenried. This piece of the puzzle had me baffled until I found the entry in the 1726 colonial record about the Meherrin.

I had re-read von Graffenried’s account over and over again, but never saw the word Susquehannah mentioned. It wasn’t until I realized that the many, if not all of the Meherrin were essentially Susquehannahs who had moved in and settled on the Meherrin river that everything started clicking into place for me.

As a descendant of some of the First Peoples of North Carolina, I have a profound interest in learning as much as I can about the history of my ancestors. I have an equally profound desire to educate others on history that has been so far untold, or unreported.

When a number of the elements of this history came together to create a much more complex picture for me, I was inspired to write about them so that others might do their own research and gain further insight and help us all have a clearer understanding of how the Indian people of eastern North Carolina (not just the Tuscarora, the term “Tuscarora War” is a misnomer) ended up being targeted in a war by the colonists. Were the individuals who were the masterminds of the revolt of September 22, 1711 from North Carolina? Were they even Tuscarora? Or did the war on the Tuscarora and their allies start because of the violent actions of outsiders brought in by distant northern relations to lead the Tuscarora and allies into battle against colonial encroachment?

Read on and see what your impression is…

Introduction

In the early hours on a cold morning in late March, 1713, the once great and powerful Tuscarora Nation was broken into pieces when their final stronghold, Fort Neoheroka, was burned to the ground by orders of Col. James Moore. In the smoldering remains of the burned fort, Moore’s forces found the virgin territory of North Carolina’s interior was no longer able to resist their invasive advances. With the defeat of the Tuscarora at Neoheroka, there was no longer an entity with the strength to prevent the encroachment, and Indian nations beyond the boundaries of Tuscarora territory no longer had the security that they would not eventually meet the same ill fate.

This marked the end of what has been referred to throughout history as “The Tuscarora War.”

Some Tuscaroras escaped the fort during the first few days of Moore’s siege and began making their way north to join the Five Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy (Haudenosaunee). Fort Neoheroka was a major blow to the Tuscarora, one from which the nation would never fully recover. At battle’s end, the Tuscarora lost more than 950 men, women and children who had either been killed or captured and taken to South Carolina to be sold into slavery. Other Tuscaroras who never sought refuge at the fort made their way to two separate reservations that had been set up to house Indians in the wake of the war.

The first reservation was Indian Woods in Bertie County (established 1717) and the second was Mattamuskeet in Hyde County in 1724. (Executive Council, Volume VII, 142) Considering that Indian Woods was in northeastern North Carolina, the territory of the “upper towns,” led by Tom Blount, who had remained neutral during the war (at least until the war’s end when he chose the colonial side and handed over Tuscarora “war” chief of the southern Tuscarora towns, King Hancock, to be executed), it might be assumed that most of the Tuscaroras at Indian Woods were from Blount’s towns and were considered by colonials to be “friendly” Indians.

The reservation at Mattamuskeet, on the other hand, was very much in the territory of tribes that remained “hostile” to colonial encroachment, even up until 1718. The Tuscaroras who made their way to live on the reservation established at Mattamuskeet would have been of the southern towns which were led by King Hancock.

The Tuscarora population on these two reservations, however, did not include the many who had never chosen reservation life, and instead went to live out in the country sides and swamplands of North Carolina’s less populated counties and frontiers.

For nearly a hundred years following the Tuscarora War, small groups of Tuscaroras made their way north from Indian Woods to join their brethren who had become the sixth nation of the Iroquois Confederacy. Just a few hundred Tuscaroras ever left North Carolina for the long journey north, and it’s uncertain how many of these stopped and settled in villages along the way, from Virginia, through Maryland and Pennsylvania, before finally reaching Haudenosaunee territory. The Tuscaroras who did reach their destination of Iroquois territory were the ones who ultimately received federal recognition as an Indian nation due to treaties that had been signed between the government and the Tuscarora nation in New York.

The Tuscaroras who remained in North Carolina became completely disenfranchised, scattering to different areas of the state, living quietly so that they might be able to survive in their homeland and not be harassed by colonials who feared them for the “warring” reputation behind their tribal name. When so many Tuscaroras chose in the wake of the war to go in different directions, they could not have possibly known that within just a few generations, they would lose their traditional ways of life, much of their culture, and thanks to necessary attempts to hide or assimilate, their language would be lost, as well. Without the shelter and protection of the Great White Pine of the Haudenosaunee, Tuscaroras remaining in North Carolina were left to fend for themselves, albeit by making the choice of not leaving North Carolina.

When the Tuscaroras’ fort fell at Neoheroka in 1713, North Carolina’s interior was opened to a colonial expansion that would continue pressing westward, displacing Indian peoples across the nation all the way to the Pacific Ocean and beyond.

So one cannot help but ask the question, “What exactly led the colonial government to declare war on the Tuscaroras to begin with?”

The Execution of John Lawson & Plans for a Revolt

In early September of 1711, the Surveyor-General of the Carolina Colony set out with Swiss Baron Christoph von Graffenried with the intention of determining a shorter route into Virginia from the area of Graffenried’s newly settled village of New Berne (so named for Berne, Switzerland), which was located on the site of the old Neusioc village of Chatawka/Chatooka at the point where the Neuse and Trent Rivers come together.

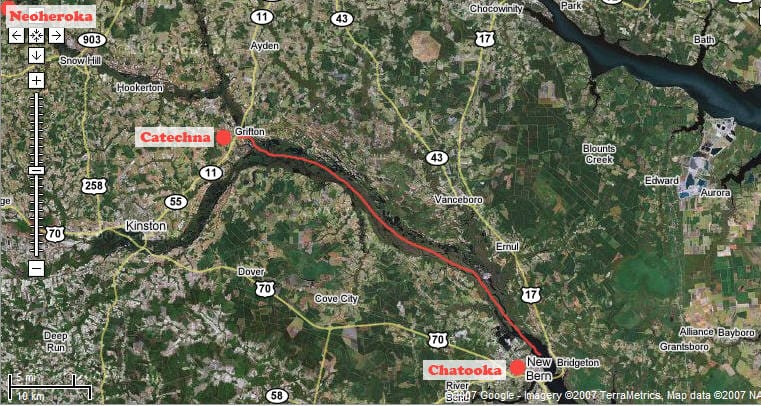

As they journeyed in a northwesterly direction, they found themselves wandering deeper into Tuscarora territory. (See map below.) Once they reached the area where the Neuse River branched off to Contentnea Creek, they were captured by Tuscarora scouts and were taken to the village of Catechna.

According to von Graffenried in his Account of the Founding of New Bern in 1710, John Lawson and himself were tried by the Tuscarora and some neighbors from other villages for crimes against the Indian people. They initially were able to talk themselves out of execution and it was agreed that they would be released the next day. Von Graffenried explained that the next day, before they were able to get into a boat to leave the village, the “king” of Cartuka (Chatooka/Chatawka/New Bern) was there and that he and Lawson began to quarrel. Later, it is explained that the man Lawson quarreled with was called Core Tom. It has long been thought that Core Tom was, himself, Coree, but if he was “king” of Chatooka, then he would have been “king” of a Neusioc village.

The argument Lawson had with Core Tom would prove to be his last. The council decided after hearing the two men argue that they would execute Lawson after all. They would have executed von Graffenried, as well, had he not begged and pleaded for his life, and, “promising everything [he] could if [they] would listen to [him] and afterward tell of [his] innocence to some of the chiefs.” (von Graffenried 267)

Von Graffenried details his grief and anxiety over the next 48 hours as Lawson is executed and he later learns that the chiefs who had gathered to meet at Catechna had decided to make war on the colonists. He reports that a few days later, “these murderers came back loaded with their booty. Oh what a sad sight to see this and the poor women and children captives. My heart almost broke. To be sure I could speak with them, but very guardedly. The first came from Pamtego, the others from Neuse and Trent.” (von Graffenried 270)

It is very important to note who von Graffenried names as complicit in this massacre of the colonists, as it can generally be agreed that this massacre is what prompted the colonials to spring into military action against the Tuscarora nation. He states:

“There were about five hundred fighting men collected together, partly Tuscaroras, although the principal villages of this nation were not involved with them. The other Indians, the Marmuskits, those of Bay River, Weetock, Pamtego, Neuse, and Core began this massacring and plundering at the same time.” (von Graffenried 270)

Note that he specifically says that there were about five hundred men, partly Tuscaroras, but that the principle villages of the Tuscarora were not involved in the massacre at all.

Considering the lack of involvement of the principle villages of the Tuscarora, and yet the apparently heavy involvement of the other coastal tribes, and considering that it appears more people were taken as captives rather than actually murdered, it seems the term “Tuscarora Massacre” is a misnomer. That aside, though, the question might be asked, “What leaders were responsible, then, for the Indian Revolt of September 22, 1711?”

In von Graffenried’s account, he specifically names the following individuals as present at Catechna:

- King Hancock of Catechna (Tuscarora)

- Various chiefs (presided over second trial of Lawson)

- Core Tom, King of Cartooka (Tribal affiliation unknown, “Core” suggests Coree, while the village of Cartooka was a Neusioc village. Interestingly, Cartooka was sold by a Tuscarora Council to von Graffenried at “Council Bluff,” which is the fork of land where the Neuse and Trent rivers come together.)

- A Christian Indian who spoke English and questioned von Graffenried as to why Lawson had quarreled with Core Tom

- Nick Major (Meherrin/Susquehannah) – This individual is not mentioned in von Graffenried’s Account of the Founding of New Bern, but is mentioned in the colonial record. (Executive Council, Volume VII, 168)

The Indian Revolt

Even in 1709, John Lawson recognized in his book, A New Voyage to Carolina, the poor way his own countrymen were treating the Indian natives of this fledgling colony. The following passages give but a few examples of how Lawson, in his own words, describes the injustices which were visited upon the Indian people of Carolina by the self-professed Christian English:

They are really better to us, than we are to them; they always give us Victuals at their Quarters, and take care we are arm’d against Hunger and Thirst: We do not so by them (generally speaking) but let them walk by our Doors Hungry, and do not often relieve them. We look upon them with Scorn and Disdain, and think them little better than Beasts in Humane Shape, though if well examined, we shall find that, for all our Religion and Education, we possess more Moral Deformities, and Evils than these Savages do, or are acquainted withal. We recon them Slaves in Comparison to us, and Intruders, as oft as they enter our Houses, or hunt near our Dwellings. But if we will admit Reason to be our Guide, she will inform us, that these Indians are the freest People in the World, and so far from being Intruders upon us, that we have abandon’d our own Native Soil, to drive them out, and possess theirs; … We trade with them, it’s true, but to what End? Not to shew them the Steps of Vertue, and the Golden Rule, to do as we would be done by. No, we have furnished them with the Vice of Drunkenness, which is the open Road to all others, and daily cheat them in every thing we sell, and esteem it a Gift of Christianity, not to sell to them so cheap as we do to the Christians, as we call our selves. (Lawson 243-244)

It was also recorded that the Indians in the newly settled region of North Carolina also had to deal with the constant fear of their children being kidnapped by the colonists for the sake of either “Christianizing” them, or making slaves out of them. In The Tuscaroras, Volume II by F. Roy Johnson, he cites that:

“The Carolina coastal tribes had suffered from kidnapping as early as the 1660’s when the New Englanders took away some children of the Cape Fear Indians ‘under pretense of instructing them in Learning and the Principles of the Christian Religion.’ New England ships, moving quietly from one Carolina river plantation to another, provided a convenient avenue for the slave traffic.

“By 1705, Pennsylvania was importing so many slaves from Carolina and other places that the fears of the Indians of that province was aroused; and the provincial council enacted a law which prohibited the importation of Indian slaves after March 25, 1706. However, many of the Carolina slaves were shipped directly to the West Indies.” (Johnson 66)

Johnson continued by explaining that concerns about wrongs suffered by the Tuscarora were brought to the attention of the Pennsylvania government at Conestoga on July 8, 1710. The Tuscaroras, according to Johnson, “presented eight belts of wampum, each signifying some grievance from which they desired relief.” (Johnson 66)

The grievances were cited as follows:

By the first belt, the older women and mothers sought friendship of the Christian people, the Indians and the government of Pennsylvania, that they might fetch wood and water without risk or danger By the second, the children born and those to be born, implored for room to sport and play without the fear of death or slavery.

By the third, the young men asked for the privilege to leave their towns without the fear of death or slavery to hunt for meat for their mothers, their children and the aged ones.

By the fourth, the old men, the elders and the people, asked for the consummation of a lasting peace so that the forests (the paths to other tribes) be “as safe for them as their forts.”

By the fifth, the entire tribe asked for a firm peace that they might have liberty to visit their neighbors.

By the sixth, the chiefs asked for the establishment of a lasting peace with the government, people and Indians of Pennsylvania, whereby they would be relieved of “those fearful apprehensions they have these several years felt.”

By the seventh, the Tuscaroras begged for a “cessation from murdering and taking them, that by the allowance thereof, they may not be afraid of a mouse, or any other thing that Ruffles the Leaves.”

By the eighth, the Tuscaroras being strangers, came with blind hopes the government of Pennsylvania would “take them by the hand and lead them, and then they will lift up their heads in the woods without danger or fear.” (Johnson 67)

Considering the abuses suffered by the Tuscarora and their neighboring tribes in eastern Carolina, it is not difficult to understand how the council of chiefs at Catechna determined to take a stand against such injustices. It is also not surprising that taking such a stand might result in the deaths of a number of colonists.

What was surprising, however, was how the “massacre” was described to have been carried out.

One incident, recounted by Christopher Gale in November of 1711 explained:

“The family of one Mr. Nevill was treated after this manner: the old gentleman himself, after being shot, was laid on the house-floor, with a clean pillow under his head, his wife’s head-clothes put upon his head, his stockings turned over his shoes, and his body covered all over with new linen. His wife was set upon her knees, and her hands lifted up as if she was at prayers, leaning against a chair in the chimney corner, and her coats turned up over her head. A son of his was laid out in the yard, with a pillow laid under his head and a bunch of rosemary laid to his nose. A negro had his right hand cut off and left dead. The master of the next house was shot and his body laid flat upon his wife’s grave. Women were laid on their house-floors and great stakes run up through their bodies. Others big with child, the infants were ripped out and hung upon trees. In short, their manner of butchery has been so various and unaccountable, that it would be beyond credit to relate them.” (Colonial Records, Volume I, 826-827)

Individuals familiar with Tuscarora traditions have often questioned the veracity of such reports, explaining that such mocking treatment of the dead would not have been compatible with Tuscarora ways, citing traditional spiritual beliefs in reference to the dead. Many remark that Tuscaroras are, by nature, far too superstitious about the dead to commit such acts as described by Gale, particularly the sort of mockery mentioned for the Nevill home.

The questions about the descriptions of the massacre have been so prevalent by Tuscaroras over the years, that many have even believed that the reports were fabricated to drum up support for a war against them at the time. Although this was possible, there is, perhaps, another explanation for this very un-Tuscarora treatment of victims.

A closer look needs to be given to the victims of the revolt, and where the worst atrocities took place. Were homes in certain areas affected more brutally than others? Were specific families targeted?

For example, is it possible that the Mr. Nevill mentioned in Gale’s letter is James Nevill who had served as Deputy Marshall at Pamplico?

Here is an item to consider (from Executive Council, Volume VII, pp 386-387):

[CCR 192]

Summons

1701 June 3

North Carolina ss. By the Honorable president and Councill.

Wheras a Warrant was Directed by the Honorable Hendeson Walker Esqr. President of the Councill etc. until Capt. Nich. Daw mr. Wm. Barrow mr. Nich. Tilor requireing them to Call to account the Bear River Indians* som of which having offerd Very great Abuse to Thomas Amy Esqr. And others with him Contrary to theire Articls made with this Government and the said Warrantt hath not been Returned.

These are therefore in his Majesties name to require and Comand you to summon the aforesaid Mr. Nich. Tilor Capt. Nich. Daw Mr. Wm. Barrow to make theire appearance before this board the third Day of the Generall Court to be holden for this province to Answr theire Contempt in failing to make return of theire proceedings As also to have before us att the same time and place the King of the bear River Indians and his great men in pursueance of theire treaty with this Government Given under our hands the 3d Day of June 1701.

Hend. Walker

Samuel Swann

W. Glover

To mr. James Nevill

Deputy Marshall att pamplico

To Execute and [illegible] returne

[Endorsed:]

These served By mee

James Nevill deputy Marshall

To Mr. [illegible]aiton – 04:02:06

[Note: *Bear River and Matchapungo are used interchangeably throughout colonial records. The Indians living at Bay or Bear River in what is today Pamlico County were of the same tribe as the Indians living on the Matchapungo River, who were called Machapungo.]

Another scenario that should be considered is the possibility that the worst brutalities in the revolt were committed by certain individuals, but this was not the message the rest of the Indians involved were trying to send.

Were there any known individuals on behalf of the Indian tribes involved with the revolt who had particularly bitter feelings towards the colonials? Were there any individuals who were known for having short tempers and very cruel dispositions?

After the next section (which is a brief history on Iroquois intertribal relations), facts will be presented on two of cases of Indian brutality towards colonials—women and children, in particular. There are a few common threads that tie these cases together with certain elements of the “Tuscarora War,” including tribal associations, as well as names of individuals. Is it possible that one or two, brutal individuals, perhaps not even from North Carolina, turned out to be the biggest instigators of the “Tuscarora War?”

Iroquois Intertribal Relationships in the Early Colonial Era

Before summarizing the two cases of interest, it’s important to give some background on the history of Indian relations in the region spanning from Susquehannah and Piscataway territory in Maryland, south to North Carolina in the early colonial era.

The Iroquois Confederacy consisted of the Onondaga, Mohawk, Seneca, Oneida and Cayuga nations. Of course after the “Tuscarora War” in North Carolina, the Tuscaroras were brought in as the sixth nation of the confederacy, which is known traditionally as the Haudenosaunee (People of the Long House.) It was very much the Iroquois way to be dominant in whatever area they were residing. Their dominance was not limited, though, to just the area where they lived, but in fact extended to the areas where they traded heavily. There was an attitude of, “Join us, trade with us, work with us, and we’ll help look out for you, but stand against us or side with our enemies and life will be very difficult for you.” It was not a particularly bullying or ill-natured policy, but rather a policy of trying to keep Indian tribes united in standing against colonial encroachment, and there was certainly strength in the numbers of the Haudenosaunee.

This manner of diplomacy was not limited only to the five Iroquois nations in the northeast, but also could be seen among the Iroquois in the south, particularly the Tuscarora.

There appears to have been a shift among Indian tribes in eastern North Carolina in the twenty year period between Sir Walter Raleigh’s first colony at Roanoke island and the 1607 Jamestown settlement in Virginia. At the time of Raleigh’s settlement, the coast of what came to be known as North Carolina was purely Algonquian. The westernmost border of this Algonquian territory could probably best be identified with the modern day US Highway 17 which runs through Elizabeth City, Washington, New Bern, Jacksonville and Wilmington, North Carolina. Beyond the Algonquian territory to the west was a land dominated by Indians referred to by the coastal Algonquian tribes as “Mangoaks” (rattlesnakes, vipers). These “Mangoaks” were actually the Tuscaroras, and possibly also the Nottoways and Meherrins in northeastern NC and southeastern Virginia (all of whom were Iroquois). It is not known whether the Nottoways and Meherrins were always Iroquois, but linguistic clues tell us that by the colonial era, they were cooperating with the Iroquois nations both to the north and the south of them. In the case of the Meherrins, the colonial records of North Carolina explain that they may have actually been Susquehannahs who had migrated south and settled on the Meherrin river:

From pp 167-169, The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Second Series – Volume VII – Records of the Executive Council – 1674-1734. Editor Robert J. Cain – Department of Cultural Resources Division of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina 1984

October the 28th 1726

This day was Read at the Board the Petition of the Maherrin Indians Shewing that they have lived and Peaceably Enjoyed the said Towne where they now live for such a Space of Time as they humbly conceive Entitles them to an Equitable Right in the same that They have not only lived there for many years but long before there were any English Settlements near that place or any notion of Disputes known to them concerning the dividing bounds between this Countrey and Virginia and have there made large Improvements after their manner for the better Support and maintenance of themselves and Families by their Lawfull and Peaceable Industry

Notwithstanding which Colollnel William Maule and Mr. William Gray have lately intruded upon them and have Surveyed their said Towne and cleared Gounds on pretence that it lys in this Government and that the said Indians have allways held it as Tributaries to Virga. which is not so Praying this Board to take them into their Protection as their faithfull and Loyall Tributaries and to Secure to them a Right and Property in the said Towne with such a convenient Quantity of Land adjoyning to it to be laid off, by meets and Bounds as to them shall seem meet.

Then allso was Read the Petition of sundry Inhabitants Living near the said Indians Shewing That Sundry Familys of the Indians called the Maherrin Indians have lately Encracht and Settled on their Land which they begg Leave to Represent with the true account of those Indians who are not original Inhabitants of any Lands within this Government but were formerly called Susquahannahs and Lived between Mary Land and <388> Pensilvania and comitting several Barbarous Massacrees and Outrages there Killing as ’tis Reported all the English there Settled excepting Two Families they then drew off and fled up to the head of Potomack and there built them a fort being pursued by Mary Land and Virginia Forces under the Comand of One Major Trueman who beseiged the fort Eight months but at last in the night broke out thro the main Guard and drew off round the heads of several Rivers and passing them high up came in to this Country and Setled at old Sapponie Towne upon Maherrin River near where Arthur Cavenah now lives but being disturbed by the Sapponie Indians they drew downe to Tarraro Creek on the same River where Mr. Arthur Allens Quarters is, afterwards they were drove thence by the Jennet Indians down to Bennets Creek and Settled on a Neck of Land afterwards called Maherrin Neck because these Indyans came downe Maherron River and after that they began to take the name of Maherrin Indians, but being known the English on that side would not Suffer them to live there, then they removed over Chowan River and Settled at Mount Pleasant where Capt. Downing now lives but being very Troublesome there one Lewis Williams drove them higher up and got an order from the overnment that they should never come on the So. side of Wickkacones Creek and they Settled at Catherines Creek a place since called Little Towne but they being still Mischievous by order of the Government Collonel Pollock brought in the Chief of them before the Governor and Council And they were then Ordered by the Government never to appear on the South side of Maherrin, They Then pitcht at the mouth of Maherrin River on the North side since called old Maherrin Towne where they afterwards Remained tho they were never Recieved or became Tributaries to this Government nor ever assisted the English in their Warrs against the Indians but were on the contrary very much Suspected to have assisted the Tuskarooroes at the Massacree. The Baron De Graffen Reed offering his Oath that one Nick Major in Particular being one of the present Maherrin Indians Satt with the Tuscarooroes at his Tryall and was among them when Mr. Lawson the Surveyor Genl. was killed by them So that these Maherrins were not originally of this Country but Enemies to the English every where behaving themselves Turbulently and never lookt on as True men or Friends to the English nor ever paid due acknowledgement to this Government. Some years agoe Col. Maule the then Surveyor Genl. obtained an Order to Survey the Lands at old Maherrin Towne which was accordingly done and Pattented afterwards since that they have paid Tribute to this Government and have been allowed by the Government to remain on those Lands. But since that a great Sickness coming among them Swept off <389> the most of them, and those that remained moved off those Lands at Maherrin Towne and sundry at them have lately Seated their Timber and Stocks and hindring them frm Improving their Lands they being unwilling themselves forcibly to Remove the said Indians least some disorders might arise thereon praying an order to the Provost Marshall That if the said Indians do not Remove off in some convenient time they may be Compelled thereto etc.

Whereupon by the consent of both Parties It is ordered in Council That the Surveyor Genl. or his Deputy do lay out unto the said Indians a certain parcell of Land lying between Maherrin River and BlackWater River Runing three Miles up Blackwater River and then a Streight Line to such a part of Maherrin River as shall be Two miles from the mouth thereof and if the same Line shall leave out the Settlement of Capt. Roger a Maherrin Indian that then the Surveyor do lay out a Tract of 150 acres the most Convenient to his Dwelling. Which Lands when Surveyed, the Surveyor is to make return thereof into the Secretarys Office that Grants may pass for the same to the said Indians. It is further Ordered by this Board that the said Indians shall Quietly hold the said Lands without any molestation or disturbance of any Persons claming the same so as the same Persons Right or pretentions to the said Lands be Reserved unto them Whereby they or those claiming under them shall have the preferrence of taking up the same when the said Indians shall desart or remove therefrom.

By the time colonists from Jamestown in Virginia began making their way down into the Carolinas to explore, the Algonquians no longer maintained the upper hand along the coast.

Whether this shift happened due to battle with the Tuscaroras and their allies to the west, or whether it was due to disease taking a toll on the Algonquian villages is not known, but there are a few clues that demonstrate the changes between the time of the unsuccessful Roanoke colony and Jamestown. In a research paper titled, “Migration Patterns of Coastal N.C. Indians” written by Fred Willard, founder of the Lost Colony Center for Scientific Research, this shift is explained:

“The primary sources from the Roanoke Voyages indicate that every time the colonists visited a new village, word would come back within ten or twenty days that large portions of the Indian population had died. From the time of John White’s last visit (1590) until the first Jamestown colonists came looking for members of the “Lost Colony” (in 1608), a dramatic change had taken place in the coastal waters of what is now North Carolina.” (Harriott 1588; Smith: 1910; Parramore: U.P.P., 1994; Shepard/Willard).

All of the names of the villages that were on the John White map from the 1585 Roanoke Voyage are documented. After the dark period, as alluded to above, all of the village names changed and the people in the villages became a totally different linguistically speaking group and culture. The Algonquians had a name for these Indians who lived to the west. They called them “Mangoaks”, which was a very deriding term meaning “they are rattlesnakes” (Shepard/Willard 2002). The Algonquians had stood their ground against these “Mangoaks” for at least a thousand years (Phelps: P.C.; Parramore: U.P.P.; Shepard/Willard), but during this twenty-year dark period (1587-1608), they underwent some kind of culture overthrow or downfall. When the colonists at the time of the Jamestown settlements (1608/1612) migrated to the south, they confirmed that they were dealing with the Tuscarora Indians not the Algonquians from the Roanoke times. It was the Tuscarora that negotiated with the Jamestown colonists who had settled the North Shore of the Albemarle Sound. The Indians drew a line east and west on the Albemarle Sound dictating a demarcation line that was not to be crossed. When the Europeans aggressively continued to cross this demarcation line, hostilities broke out. The disputation finally culminated in the outbreak of the Tuscarora War and the Tuscarora’s defeat at their Nehoroka Fort in about 1714 (Parramore: U.P.P.).

To the north in the territory of present-day Maryland and Virginia, a similar series of events was occurring with the Haudenosaunee (usually the Senecas are named in the official records, although it was common practice in those days to use Senecas to describe any of the Iroquois of the Five Nations), the Susquehannahs and the nearby Piscataway tribe (indigenous to southern Maryland).

The Susquehannahs and Senecas are reported to have had a good working relationship, both nations standing strong against aggressive colonial encroachment. The Piscataways, on the other hand, had taken a much more passive stance towards the English. An article titled, “The Migration of the Piscataways” from Landmarks of Old Prince William suggests that perhaps this was due to the fact that in the mid 1600s, the Tayac (“emperor”) of the Piscataways was converted to Christianity and baptized. His daughter was taken to St. Mary’s (Maryland) and, herself, baptized and educated by the English, thus making her, “the Maryland Pocahontas: as we have seen, she married an Englishman, Capt. Giles Brent, then of the Maryland Council, and with him reared a dusky race. In 1666 the Maryland government cemented this relationship by making a formal treaty with a successor Emperor and henceforth, the Piscataways were tributaries.” (Harrison 94)

This loving relationship between the Tayac of the Piscataway and the English was certainly worrisome to the Senecas and Susquehannahs. The strained relations amongst these nations peaked when the Piscataways fought alongside the Maryland troops in the Susquehonnock War of 1676. According to Harrison, this earned the Piscataways the hatred of the Iroquois, which in 1680 forced the Piscataway to request permission to move back to a territory to live amongst the Marylanders where they might feel greater safety from their tribal enemies. This safety, however, did not endure. It was not long before the Piscataways moved back into the county of Old Prince William in Virginia:

A location was found for them in Zachaia Swamp, on what is now called the Mattowoman Creek, In Charles County, but even there they had to withstand a siege of the Iroquois in 1681 while Maryland hesitated about going to their assistance. At the treaty of Lancaster in 1744, the Iroquois maintained that they had conquered the Piscataways as well as the Susquehonnocks, but it does not appear that in both cases they did so in the field.

It seems it was the practice of the Maryland Indians to poach in the Iroquois hunting preserve in the interior of Old Prince William and, undoubtedly, during the decade after the unsuccessful siege of Zachaia fort, whenever the Iroquois caught them in Virginia, they ruthlessly cut them off; but the ultimate subjection of the Piscataways was accomplished more by guile than by arms.

The Long House taunted them with the failure of Maryland to protect them in 1681, and pointed out that they were becoming mere women living surrounded by the English, and beaconed them to join forces with those who could and would make men of them.

By the end of the century theses temptations became resistless. The Emperor complained to the Maryland government that he was unable to control his young men; that they were being seduced by evil influences. Eventually radical counsels prevailed at Zachaia and the whole tribe abandoned Maryland. Suddenly and without warning, but, of course with the consent of the Iroquois, the Piscataways moved across the Potomac and into the back country of Old Prince William, and thus came into direct contact with the Virginia government. (Harrison 95)

The reason for the move of the Piscataways back into the territory of Virginia leads directly into the court cases alluded to in the previous section.

On the Trail of Tom

In 1697 in Maryland, a Pamunkey Indian called Esquire or Squire Tom, is indicted for the assassination of the wife and children of one William Wigginton of Ocquio. The case reveals that Squire Tom had been contracted to do the crime by Susquehannah and Senecas.

An Indian identified as Choptico Robin in the Proceedings of the Council of Maryland, 1696/7- 98 (pp 187-188) gave the following testimony as to the events that transpired leading up to the crime:

Early in the Spring to witt about 5 months last past Esq Tom was at or about the ffalls of Potomock and there were some Piscattoway Indians & some of those Seniquos that live in the mountains amongst which last was a Susquehanah a great man whose name is monges, this Indian had much private Communication then with Esq Tom, wch noe other Indians knew or noted, he presented him with a large belt of Peak, and told him that his Nation was Ruin’d by the English assisted by the Piscattoway’s, & tht now they were no People, that he had still tears in his Eyes when he thought of it and not being able to doe any thing in Publique he must take his Revenge in private by his money & therefore if this Esq Tom would kill some English where he Could with greatest Safety doe it and most probable to be lay’d upon the Emperors People, he would give him great Rewards it Carrying with him a double Revenge for that the English would ffirst bleed & then Revenge it upon his Indian Enemies also this Esq Tom promiseth to do & Communicated to this Robin who as he Sayth diswaded him but promised to keep his Councill.

The thing was proposed to be Comitted in Maryland but he having Denied his Assistance Doth not know if the Negro kill’d were done by Esq Tom however tht action Caused both the Emperr & Pomunkey Indians to ffly to Virga tht the Emperr sate down there where now he is but the sd Pomunkeys soon Return’d to Maryland tht he Coming from Choptico about the time Esq Tom & his Gang Came over to hunt he was perswaded to Come with them to Virga that being so Come & in the Wods a little beyond my house Esqr Tom on a Suddain told him he would kill some English and since he had known his design, If he Refused to goe with him he would kill him as believing he design’d to betray him so tht this Robin the Relater with Esq Tom & one Indian more Rann back from their Company & Esq Tom & the other Indian did the Mischeif & this Robin kept Sentry, that all the Rest of tht Company knew of the thing only the Deafe Indian and him they did not acquaint, Sr pardin the prolixity that Necessity Drawes Naratives under & Accept the Zeale of Yor most humble and Obedient Servant

Geo: Brent

According to Harrison, “Tom had been spirited away by the Iroquois and disappeared forever from the stage of history.” (95)

But had he really?

In July of 1699, the Maryland Assembly Proceedings record reported that, “The Indians say that Esqr Tom is with the Emperor of the piscattaway.” (329)

A thorough search through the Maryland Archives reveals no further information about the fate of Esquire Tom, but just five years later in Virginia, several Indians from St. Mary’s Parish, including one named Long Tom and another named Qualks Hooks, were indicted for brutally murdering a white family. Everyone indicted (except one individual) was sentenced to hang. So far, no evidence has been found indicating any of the executions were actually carried out.

Virginia is not known for always carrying out assigned death penalties. There are numerous examples of men who were sentenced to hang, who later show up still living free in other places. (Some of Blackbeard the infamous pirate’s men are just a few who were fortunate enough to escape Virginia executions.)

Below is an accounting of the crime that transpired:

Young Tom and Qualks Hooks being duly examined what they know of the murder of John Rowley, say that on Wednesday the 30th day of August last the said Tom and Qualks Hooks went along with other Indians (viz.) Young Toby, Long Tom, and Jack the Fidler (who pretended they were going a hunting) to the house of George Phillips and there they did meet with other Indians(viz.) Old Mr. Thomas, Bearded Jack, Tom Antony, George and Frank, and from the said George Phillips the said Tom and Qualks Hooks went along with the aforementioned Indians to the plantation of the said John Rowley, the said Indians sat down and Bearded Jack, Old Mr. Thomas , Tom Antony, Jack the Fidler and Long Tom presented themselves and the aforesaid old Mr. Thomas, said to the other Indians let us go the house and get some victuals, and when they came to the house John Rowley was in the loft and two women and a girl was in the lower room and Old Mr Thomas asked the said John Rowley to come down and pipe it, when said John Rowley came down and the old Mr. Thomas shook hands with him and asked him how he did and whilest Old Thomas talked with the said John Rowley, Tom Antony held the said John Rowley and old Mr. Thomas struck him with his tomahawk and knocked him down, and Qualks Hawks asked Old Mr. Thomas why he killed the Englishman and then the Old Mr. Thomas run after the said Qualks Hawks with his tomahawk talking Indian which he did not understand and the said Qualks Hawks run away from him, and after they had knocked the said John Rowley down the said two women run away and Bearded Jack and Jack the fidler run after them and Jack the Fidler knocked the young woman down and skinned her head and Bearded Jack knocked the old woman down and skinned her head, and Jack the Fidler took the child and said he loved children and held the child between his legs and stuck her like a pig, thrusting his knife in at one ear and out of the other, and that Old Mr Thomas after they had killed the two women and the child said, come let us go into the house and look for some goods, and they then said Tom and Qualks Hooks went away.

Young Toby, Jimmy, Harry and Capoos, other men who had been brought in for questioning regarding the case all verified the above testimony when they were examined before the court, with only minor additions to the testimony. When another man, Mattox Will was questioned about his knowledge of the murder, he explained that Bearded Jack had confessed to the crime and stated that he did not care if he was hanged for it. He continued his testimony with an interesting detail:

The said Mattox Will being asked what he knows about any Younger Indians said that three months ago Bearded Jack told him there was about one hundred Indians (illegible) come down the mountains and saw (illegible) by the (illegible) and that now were exported down and asked him corn was ripe, they would fall upon the English and that the Piscataway Indians would join with them, Bearded Jack and Tom Antony affirm the same before us and that they heard it in Maryland.

Long Tom being examined said that it was his fathers fault who persuaded him along with them and that all the young men and the boy have said is true, and that all the (illegible) Bearded Jack, Old Mr. Thomas, Tom Antony, Jack the Fidler, Frank and George were guilty of the attack and himself of being with them, but that he did not help to kill the English which the rest say as true, ant the rest would tomahawk him if he would not go with them, and he also says he heard Tom Antony and Jack Beard say what is formerly related to of the (illegible) Indians.

It is not apparent to which tribe the Indians involved in this case belonged, but the mention of Indians coming down the mountain is reminiscent of the Senecas from the earlier case. It is quite possible that the men charged in this case were Susquehannahs, particularly since the Iroquois did ultimately succeed in getting the Piscataways to side with them after the Squire Tom murder case of 1697. More research is needed to determine to which tribe these men belonged.

The names in this 1704 case are striking. Long Tom is mentioned as a defendant in this case, but Long Tom is also the name of one of the chief men of the Mattamuskeet reservation in the period after the Tuscarora War. Qualks Hooks is a name also mentioned in the 1704 case. Square Hooks or Squire Hooks was the name of a Tuscarora “war chief” mentioned in the Peace Treaty of 1712. His name in Iroquois (exact language uncertain) was Oun-ski-ni-ne-see. Furthermore, John Squires was “king” of the Mattamuskeet Indians until the mid 1700s.

It has often been thought that Core Tom (the “king” of Cartooka/Chatooka who was present at the trial and subsequent execution of John Lawson) was a Coree chief, but it is a known fact that Cartooka was a Neusioc village. The evidence points to an alliance amongst the Tuscarora and the Neusioc, the Coree, the Matchapungo (including the lower Matchapungo at Bay River) and other coastal tribes that would not have been unlike the alliance that was in place amongst the Iroquois in the north and the Susquehannahs, the Piscataways and other neighboring tribes.

Is it possible that the Core Tom at Catechna and Long Tom at Mattamuskeet are one in the same? If so, then is it possible that the Long Tom at Mattamuskeet is the same as the Long Tom in the 1704 Rowley murder trial? Is it possible that this same Tom may be the Squire Tom of the 1697 case? The use of these names, which are popping up in Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina, in subsequent years, is quite a remarkable item of interest. The fact that these names showing up as they do along with the tribes that they show up with is even more interesting.

Considering that the Meherrin were identified in that 1726 colonial record item as actually being Susquehannahs demonstrates a strong Susquehannah presence in North Carolina at the time of the war. The fact that the traditional Susquehannah territory was in Maryland and extended up into Pennsylvania is also of interest, particularly considering that a faction of Tuscarora in North Carolina had sent the eight rows of wampum to Conestoga in Pennsylvania (Susquehannah territory) to try and seek a safe place there.

The clear Susquehannah connection between the Iroquois in the north and with the Tuscaroras in North Carolina, especially at Catechna, considering a Meherrin (Susquehannah) named Nick Major was cited as being present at the trial of John Lawson, and was also there for the planning of the attack on the colonials in 1711.

Here is a scenario that this author will be investigating further (please note, this is only a hypothesis and in no way represents a factual statement of certainty regarding these events):

In 1697, an Algonquian Indian of the Pamunkey tribe Esquire Tom (or Squire Tom) was offered an opportunity to make a name for himself by a Susquehannah named Monges, accompanied by some Senecas. Monges asked Squire Tom to murder some white people and then cast the blame on the Tayac (emperor) of the Piscataways, because the Susquehannahs and Senecas were very angry with the Tayac and his tribe for siding with Maryland colonials in a tense time of colonial encroachment. Squire Tom did cast the blame on the Tayac when he was caught. Even though he had committed this crime and laid the blame on the Tayac, the Piscataways felt enormous pressure to join with the Iroquois tribes in their stand against the colonists, and so ended up taking in this Squire Tom to hide him from the punishment he would receive if he ever were to face his murder charges. This way the colonials would have known that the Tayac was not responsible and that Squire Tom was, but that they would be unable to go into Piscataway territory to take him.

Seven years later, in 1704, the same Tom is living amongst a tribe that is friendly with the Piscataways, and therefore most likely also working in cooperation with the Iroquois. Due to hostility, Tom, along with several men from his community, go to the home of John Rowley, where the men kill Mr. Rowley, two women and a young girl. The women’s heads are skinned and the child is brutally murdered, as well, being stabbed in the head.

It should be noted that in the 1697 case, Squire Tom and his accomplices cuts Mrs. Wigginton’s breast up and skins her head, and according to one report, she was stabbed in the side of the head. The children were also wounded in this attack.

The record shows that Squire Tom of 1697 was never caught and punished for the murder he was alleged to have committed. As for the 1704 case, although the men were all (but one) sentenced to hang, there is no evidence that any of them were executed.

Would it have been possible, then, that they would have been “spirited away by the Iroquois” again to be put into a useful position in North Carolina, where tensions between the Tuscarora and the colonists were heating up, and the Susquehannahs had already found a comfortable home? Is it possible that Core Tom was handpicked and put into a power position as a war chief over the Neusioc and the Coree, and that he was one of the masterminds behind the massacre, or revolt of September 22, 1711?

Is it possible that the Qualks Hooks mentioned in the 1704 case is one and the same as Square/Squire Hooks who was named as a Tuscarora war chief in the 1712 peace treaty? Is there any connection between John Squires, king of Mattamuskeet, and Square/Squire Hooks?

What about between John Squires and Squire Tom? Particularly since the two men who ended up establishing and running the Mattamuskeet reservation were John Squires and Long Tom.

Much more research needs to be done, but it is clear that there is some very interesting history that has not yet been told, and much more that will be added to this publication as new facts are uncovered.

Works Cited

Archives of Maryland, Volume 022. Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly March 1697/8 – July 1699: March 8, 1697/8 – April 4, 1698 (http://www.msa.md.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc2900/sc2908/000001/000022/html/index.html)

Archives of Maryland, Volume 022. Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly March 1697/8 – July 1699: June 29 – July 22, 1699 (http://www.msa.md.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc2900/sc2908/000001/000022/html/index.html)

Cain, Robert J., ed. The Colonial Records of North Carolina [Second Series] Volume VII: Records of the Executive Council 1664-1734. Raleigh, N.C., Department of Cultural Resources, Division of Archives and History, 1984.

Harrison, Fairfax. Landmarks of Old Prince William: A study of origins in northern Virginia. Richmond, Va.: Old Dominion Press, 1924.

Johnson, F. Roy. The Tuscaroras: History, Traditions, Culture – Volume 2. Murfreesboro, N.C., Johnson Publishing Company, 1968.

von Graffenried, Christoph. von Graffenried’s Account of the Founding of New Bern. Ed. Vincent H. Todd, Ph. D. New Bern, N.C., John P. Sturman/Bern Bear Gifts, November 2003.

Willard, Fred. “Migration Patterns of Coastal N.C. Indians” From website of The Lost Colony Center for Science & Research. (http://www.lost-colony.com/research.html)